“Being autistic doesn’t mean you fit into a box, it means you are on this very wide spectrum of what is possible.”

-Brandy Haberer

Trigger Warning: This article contains material that may be harmful to readers. Mentions of suicide and harmful experiences in mental institutions.

At my last visit, my dentist told me that I needed to have all four of my wisdom teeth removed. When I asked her how long I could wait before getting the surgery, she said, “Don’t wait too long. Our bodies only get worse at adapting as we age.”

When Brandy was told that she had autism, she was in her late 30s. An age when most people have learned to live with life. Brandy had too, in many ways, learned to live with an autism that she didn’t know she had. Specialist after specialist had misnomered her reality. Without a proper medical diagnosis, the appropriate care, and knowledge ofwhat measures to take when the going got tough, the experience became harrowing. As Brandy and I spoke about her experiences being on the spectrum and dealing with chronic illness, she reminded me of the importance of medical humility. Providers are often lauded as Gods and it has been equally said that you need to have a little savior-complex to be good at holding other peoples’ lives in your hands. But during the interview I couldn’t help but wonder if not listening to your patient and not understanding that, despite your vast education you may have, there is always something to learn, is in direct violation to the physician’s manifesto, “Do No Harm.”

As Brandy taught me about a side of neurodivergence and Ehlers Danlos Syndrome I never knew existed, I noticed that I was involuntarily jotting down a list of things I would need to Google after I stopped recording. For everything the world may have considered as her weaknesses, I have never met someone as in tune with and as self-aware about their body as Brandy. I hope learning from her leaves you a better person, as it has left me.

.

D: I always prefer to start off these conversations a bit like a job interview. I’ve never really known how to answer this particular question for myself, so I love to hear what other people have to say. So Brandy, tell us a bit about yourself!

B: Hi! So, my name is Brandy Haberer and I like to say that I am an autism and disability rights activist. My husband is also autistic and we run a wonderful podcast together. We have a page called the Chronic Couple with several social media platforms where we try to spread the word about late diagnosed autism and people with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome – just get these conditions and their realities out there. I am also the community manager and social media manager for an autism social app called Hiki, which creates virtual spaces for people on the spectrum to meet each other and form all kinds of wonderful relationships

D: So you run the Chronic Couple Podcast which is both a brand and an actual podcast. And you and your partner are specifically focused, in your content, on individuals diagnosed with autism at a later stage of life. Now this is super interesting because as a “grown up,” you’ve lived your whole life accepting some warped version of your own normal, living with certain labels you have ascribed to yourself and that society has given you— and then poof one day things are very different, except now you’re 30!

B: When I first found out I was autistic, I was shocked and I mean shocked! Well, I guess, parts of it made so much sense, and it’s almost like I knew somewhere, but I was still so overwhelmed and confused with how this could be and what it all meant! My mom had worked in special education for a long time at this point and even she was like “How did I miss this?!”

I think my partner and I don’t “look like autistic people” sometimes. We don’t behave the way people expect us to behave. People are always like “you’re so normal!” But being autistic doesn’t mean you fit into a box, it means you are on this very wide spectrum of what is possible. And so we felt like we had this duty almost, to talk about our truth and educate people.

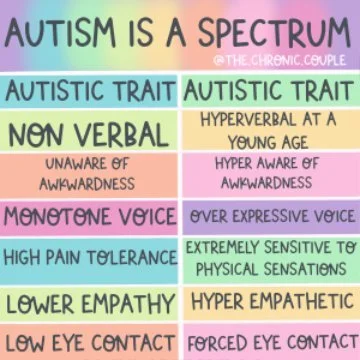

Autism is a Spectrum

D: Can I just say how beautiful that is? Not the counselor bit, but the way you reframed that penultimate thought. I think the whole “multiple, fast-paced interests” aspect is largely perceived as a weakness with ADHD. But the way you just re-owned that and said “I’m constantly interested in new things and that is kind of cool.” I love that.

And I want to use this idea of reframing expectations to focus on the fact that you were told you had autism very late in life. For reference, the average age of diagnosis is around 3. You were in your 30s.

B: Late 30s!

D: Right. And you talk a lot about the signs of having ADHD and autism that seem almost too obvious to you now. But I’m getting the sense that MANY medical professionals missed these insights in the past. Can you tell me a little bit more about your experience with misdiagnosis?

B: In school, I spent a lot of years being so afraid that if I was myself, if I acted like myself, people wouldn’t like me and that they would be highly annoyed with who I was. So, my natural tendency for a very long time in life was to find the person that everyone liked and copy their behaviors. I didn’t realize I was masking in this way. It was very unconscious. And I was so good at masking and pretending to be someone else, that I was diagnosed with things like borderline personality disorder, bipolar disorder, just a slew of things that weren’t what I had. No one even suspected autism because I acted so well.

In the 7th grade, I couldn’t go to school anymore. I was losing my mind. At 15, I tried to commit suicide. I was so misunderstood. When my parents took me to the emergency department, I was asked, “Did you want to kill yourself?” When I said “yes,” because that was the truth, I was instantly handcuffed, put into the back of a cop car, and taken to a facility downtown, an hour away from my home. I had everything taken off me when I got there. I was watched while taking a shower. I had people just line up and shove meds in me. I didn't know what I was taking and the pills just made me into a zombie. This was my first experience being “misdiagnosed,” I guess— just being treated like an animal.

I couldn’t do therapy for most of my growing up years because my parents did not have medical insurance for me. When I was in my 20s and could pay for it myself, I gave it a shot and I was immediately misdiagnosed again with bipolar and given a whole host of meds which made me feel awful. It wasn’t until my 30s that I tried therapy again. This therapist originally missed my reality too. She threw in OCD, ADHD, the regular rotation that had already been presented to me time and time again, until one day, she said “You remind me of another client I have who has Asperger's!” It’s an outdated term now, but this was a trigger enough for me to go down the Google rabbit hole. I presented it to her. “Was this something I could really have?”

So I decided to go to an autism assessment center. And let me tell you, this is a very hard thing to find as an adult. Everyone wants to do children’s evaluations, even the tests I did end up getting were clearly made for kids. Flash cards and coloring books and blocks and toys— I remember being so discouraged because I almost did not get my diagnosis. My tester seemed to think it was impossible because I somehow could carry on a two way conversation or make eye contact

D: Oh!

B: The person who diagnosed me was not educated enough to realize that I was masking That I had been doing it all my life. She has never heard of someone who was on the spectrum who could be a professional singer. But I had been! She just wasn’t able to see past the textbook traits that I think a lot of “experts” are referencing and that almost cost me my diagnosis.

D: And even beyond the masking, from this story it seems like there were several instances in your life where you were very clearly asking for help. Where your body was quite physically trying to draw attention to the fact that you needed some guidance and you were still unable to get it from the medical community.

B: People don’t realize that there are polar opposites of what is possible. Individuals can be anti-social or they can be hyper social. They can be unfocused or hyper focused. There are as many types of autistic people as there are neurotypical people. It was very hard for me to become a professional singer. I would have a panic attack every time I performed. I had to wear earplugs on stage. I would go home and die from sensory overload after every performance! It is hard for us to do these things, but we can do them. Medicine doesn’t give us enough credit really.

D: I will say that as someone who is becoming a part of medicine, and who is not on the spectrum, autism is presented and viewed as a necessary handicap by many. Which it is not! It’s just a way of being, as you talk about a lot. And you would never try to box neurotypicals the way we do neurodivergent people. It sounds like we throw around the term autism “spectrum” a lot, but practically I wonder if we are really teaching and appreciate the blurriness and gray of the spectrum.

B: Yeah there are so many traits on the spectrum and each of those traits is on its own spectrum!

"There are as many types of autistic people as there are neurotypical people"

D: So that brings me to my next question. What was it like navigating the American healthcare space as a person on the autism spectrum? Whether it’s coming in to the clinic for a physical, a dentist appointment, a therapy session, a pap smear, a vaccination, a mammogram. Hospitals can be very stimulating environments.

B: It’s been hard. It’s been very, very hard. Especially having Ehlers Danlos syndrome, a connective tissue disorder, you just fall down all the time, you sprain your joints often— I was constantly sick, waking up with mast cell activation and wheezing. I was always in the ER. And it was an anxiety provoking experience, with all the lights and the sounds and the movement.

I also have a lot of rare conditions. Which means every time I go into the ER, even for an EpiPen, I would have to explain to the doctors what my body works like. Especially early on, I would have to explain the science to them because they couldn’t figure out this odd sounding condition that they had never heard of. I have to quite literally tell them, I have this and this is how it is spelled and it’s surprising, but a lot of doctors don’t like that very much.

D: “Don’t tell me how to do my job!”

I think in medicine there is a stereotype of the Googler – The patient who has been on WebMD and thinks they have all the answers. And while I hear how that can be frustrating to some doctors, I think that troupe has been very unfair to a lot of people who are just exercising their right to research and advocate for their bodies.

B: With my EDS, I actually figured out I had it myself. I had seen a lot of people with mast cell activation, which I did have, who were also hypermobile, and had Ehlers Danlos. I did some reading and found that a lot of the traits fit me. But when I went to my doctor about it, he first googled what I was saying, then moved two joints in my arm and decided that because I wasn’t in a wheelchair or affected severely, that I didn’t have it. It’s that analogy in medicine of “if you hear hoofbeats think horse, not zebra.” Well sure, I see where you are coming from, but that does make it very hard when you are a zebra and you are already largely unseen by the system.

D: Fair enough that an ER doctor may not always know the rarest of rare conditions. They are human too. But I think that any provider owes it to you to give your idea the time of day or at least write a referral, call in an expert, do more research, anything to validate your gut feeling. And this goes back to being a young person, without the power of an official diagnosis backing you. How did you carry this burden of having to be the gatekeeper of your complicated medical situation at such a young age?

B: When I was 15, I was going into anaphylactic shock at least once a month. I was covered in hives. I was allergic to everything. Allergists and immunologists could not figure out what was going on with me, so they would keep upping my prednisone dose. At one point they even wanted to put me on chemotherapy to “restart” my body. My mother was, understandably, very against this, and she had put me on an experimental drug trial that somehow, miraculously worked and took away my hives. At the time, they labeled my condition Chronic Idiopathic Urticaria Angioedema. As a young person, this is what I would have to explain to every single doctor at every single ER visit or new office appointment. I could see their eyes glass over as I would go in with my symptoms and tell them my diagnosis, only to have them respond “You have a cold! And you’re fine.” All I would think during these visits was “No you don’t understand, I can’t breathe! Please help!”

And for the EDS, it took me three more years to get diagnosed. I would go from doctor to doctor and beg for a referral to see a specialist but people would keep telling me that what I had was too rare to be real. That I wasn’t injured or handicapped enough to have it. Also, there are only a handful of doctors in the world that are specialists in the condition and I was lucky enough to find one that I was able to go to, but even she had to quit right after I joined her clientele because her pain levels were too high. I remember all her patients were so devastated because she was the only doctor any of us had known who would prescribe us narcotics at the level we needed to get on with the day.

D: Right, because she had EDS herself, so she understood?

B: Exactly. I could not move my neck. I could not move my arms. I was in physical therapy for 6 months. But no one would give a 20-year-old pain medication that was stronger than Tylenol. I will say though, now that I have my official diagnosis and it’s on my chart no matter where I go, I don’t get any questions. I don’t get looked at like a drug seeker. My doctors acknowledge that they don't know what EDS is but that they are willing to learn.

D: That is the power of diagnosis. The power of that medical label. And it’s almost as though if you don’t have that, you don't matter. But once you do, the whole world opens up. And even with therapists and psychological care in general, today there is this concept about being “trauma-informed.” Being uniquely trained to look at life and it’s circumstances through that trauma lens. Have you ever felt like your providers have been autism or neurodivergence informed?

B: I don’t think I’ve ever met anyone like that in medicine. It sounds so cool when you are saying it! I once heard someone say that autism evaluations and assessment should only be done by autistic people! And while it was a joke, I think there is some truth to that informed perspective. Because now that I know what I have, I can so easily identify it in other people. We can see who around us has the same traits. There have actually been so many doctors that I have gone to in my life to whom I’ve wanted to scream “By the way, you’re probably on the spectrum! Get informed!”

D: It’s so interesting that you bring that up! Because I am wondering about the medicalization of autism as a condition. Does the medical community view it as a disease that needs to be treated?

B: I think this goes back to what we think autism means and what it looks like. When I was first diagnosed, my parents and I couldn’t really believe it! Because you’re right; I looked and behaved “differently.” But even with school and my issues in that realm, I always said to myself “it’s not that I’m not good at math, or that I’m a terrible student in certain subjects; I just wasn’t given the proper tools to learn math in the way that I needed because the instruction was developed for a certain kind of neurotype.” Being neurodivergent does not make you disabled. It is the fact that society looks at you a certain way because of your neurodivergence that makes you disabled. If things were better set up to accommodate your uniqueness, then it wouldn’t feel so disabling!

D: And with that, I think we would be remiss if we didn’t speak about COVID and how the pandemic has affected you and your relationship with healthcare and health-seeking at the intersection of your various identities.

B: It’s strange, it’s like in a way it was really scary because with EDS your body is constantly breaking. I wasn't able to go to physical therapy. I wasn’t able to go to the ER because I couldn’t get COVID. I kept telling my body to hold on for a few more months, which then became more months and more months and it got to the point where I was neglecting the care I needed for my other conditions.

D: I think that is one of the biggest public health challenges to come of this period, outside of COVID, is that it seemed like for a long time, every other health concern took a back seat. Even regular checkups and screenings; everything started coming secondary to getting basic care.

And in that vein, if we look at how hospitals are set up, the infrastructure of healthcare, the clinic flow, the nature of appointments, what have you— how do you think that medicine today can better accommodate neurodivergence?

B: I would definitely say that when I’m in a hospital I can barely breathe. The scents of the cleaner and the sanitizer, it’s all too much for me. I don’t know if there is a scent free option that they can use or not.

D: Well they can at the very least provide masks, beyond COVID, recognizing that the smell is not for everyone. And it would not just be for people with autism, pregnant patients, for instance, have a very strong aversion to smells.

B: That is a great point. I also think the hospital lights are so bright and white. They are harsh really. And I know you definitely don’t want to be missing anything important in a hospital and those lights are probably important.

D: But at the very least rooms should have dimmers or some kind of control that the patient is given to make their stay more relaxing and ultimately promote their health and well-being.

B: And I would say, I know this sounds bratty, but usually when I am in the waiting room, I’m in a lot of pain. This is along with other people who are also having a tough time of course, but with the commotion and the presence of so many other individuals, and the weird noises and smells, I am usually on the brink of a breakdown. It would be so nice if there was an area of the waiting room that was more sectioned off for people who needed some space during all of that.

"Being neurodivergent does not make you disabled. It is the fact that society looks at you a certain way because of your neurodivergence that makes you disabled. If things were better set up to accommodate your uniqueness, then it wouldn’t feel so disabling!

D: I would say especially in a therapy suite or a psychiatric office/emergency room, that would be prudent. And even in regular emergency rooms, an overwhelming amount of patients are psychiatric. People not really knowing where to go and in crisis, approach ERs across the country. We do not want to be exacerbating their pain by crowding them with a bunch of other people.

B: I was in TMJ therapy once and it was in a very open room where I could see everyone else receiving their treatment, being in pain and what not and it was really overwhelming me. I had a lot of anxiety during that visit. But even just asking the therapist to curtain off the area I was in so I wouldn’t have to physically watch other people go through their care did so much to help me feel better equipped and in control.

And in general—and oh gosh, I don’t even know if I should say it.

D: You’ve earned the right, I say go for it.

B: Well, if you have a patient who comes in and it seems like they’ve been here a time or two before and they seem like they know what is going on with them, just believe them. Don't throw out the “I see someone’s been on Dr Google!” line. I’ve had that happen so so many times. This defensiveness almost— “Let me do my job!” And I understand that, I do , and I’m not trying to undermine you, but I do know a thing or two about my condition and advocating for myself has saved my life before. People have put me on drugs in the past that I can’t take! I was once prescribed something that gave me intracranial hemorrhage! It’s because I have taken the time to google these medications and its triggers that I know how to protect myself.

D: And recognize that it’s not coming from a place of “I know more than you” but one of I’ve been forced to advocate for myself for so long, I just feel like I have to in order to protect myself. And the purpose of Auxocardia and this column is to educate future medical professionals on how we can be better! What would you like to say to future doctors, future PAs, future nurses, paramedical professionals, and so on?

B: I think it’s so fascinating and so wonderful to be a healer! Don’t ever forget why you started doing what you are doing. That way, when you do get that difficult patient or the “know-it-all,” or when a situation is really hard, you might be able to come back to that place of humility and not be defensive and miss something. You will have hard days, but don’t become jaded and bitter. Especially like some of the older specialists I had interacted with. The ones who didn’t listen, didn’t really want to know more, who just wrote things down, and pushed me out the door. Sometimes I would feel like the only way I could get a test run was if I was downright annoying.

Don’t ever let your patients get to that stage. Instead, use moments of distress in your career to go back to your why.

Medicine is a puzzle and you probably signed up for the zebras not for the horses.

Photo Credits

-

Licence: Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0)

Credit: Cajal Neurons.

Odra Noel.

-

Provided by: Brandy Haberer

She and her husband can be found here